It was meaningful to hear from Kathy Cunningham as she shared her experience attending the recent IBPI Bikeway Design Workshop hosted by the Transportation Research and Education Center at Portland State University. Vision Zero advocates gathered over drinks and food on Thursday, November 2nd for the most recent Happy Hour presentation. Thank you to Humble Monk Brewing Company for hosting us!

Kathy Cunningham, PhD (she/her) is President of Queen City Bike, a grassroots, 100% volunteer cycling advocacy organization that works to expand bike access, skills, confidence, and community through numerous bike-related events and resources.

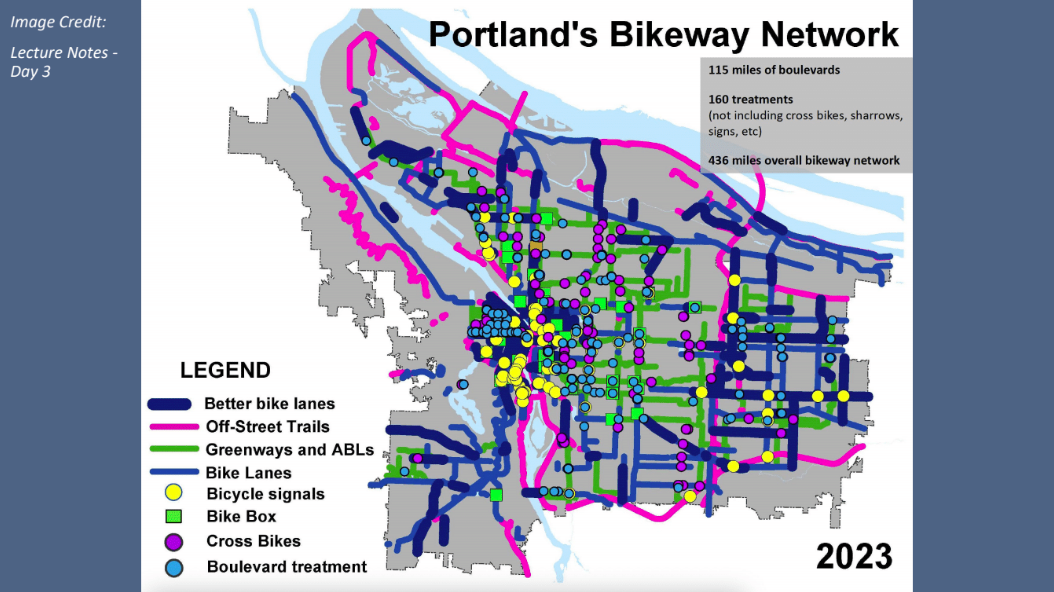

Portland is widely admired as a cyclist’s dream, with a depth and quality of biking infrastructure that surpasses most other US cities.

Cunningham zeroed in on three questions:

1) What is it like to bike in Portland? 2) What can we learn from Portland’s methods and strategies? and 3) What can we translate to challenges in Greater Cincinnati?

Bikes have always been a source of freedom and joy for Cunningham: “Just a little background on me, I’ve always loved bikes.” *cue the adorable childhood bike photo*

Cunningham shared a ton of imaginative resources that can’t all be covered in this recap—watch the livestream here!

What is it like to bike in Portland?

After giving some historical background on Portland and asking if people had been to Portland and their overall impressions and professional backgrounds, Cunningham shared her own impressions with themes bolded in her powerpoint:

“For me, this was the first time to just really be able to do a lot of riding in Portland, so especially the first few days, you know how it is, anytime you go somewhere new…you are kind of flooded with impressions.

And one of the things I loved most about being in Portland was how empowering it was to be able to get around on a bike and to not have to use a car.”

“So, I had left Cincinnati–I used Metro and TANK to get to the airport. I had my backpack and my duffel bag and my bike helmet. I used an airplane; landed at the Portland airport, hopped on the bus and the light rail, got to the old part of Portland, picked up my bike (thanks to Devou Good for providing the bike!) and then I got to the hotel and I stopped and I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, I made it [to Portland] without having to use a car the entire time.’

And this was new: to be able to figure out all of those pieces the first time. Really putting it all together speaks to how possible it is, right? It’s empowering that you can do things that might just be impossible to do in another location.

I also found it incredibly welcoming: this kind of blew my mind as I was at the airport walking under the signs–there’s a bike assembly area! And I was like, wow, I love this place. Right? How many cities, Cincinnati included, you go to the airport and it’s like, there would be no point in assembling your bike at the airport because you cannot go anywhere from [the airport] on your bike.

So! A dedicated bike assembly area at the Portland airport, and there’s a good reason for that because [while they are currently doing some renovations], normally there’s a light rail right at the airport, and the light rail allows bikes on the trains.

I also had lots and lots of feelings of liberation riding around. So much of it had to do with the feel of the streets: often in an urban environment or in a lot of traffic stress areas, you feel that constant pressure, pressure, pressure.

And here [in Portland], there’s lots of cars, but because of the way that the streets are designed, you’re just like, this place is meant for bikes. You can actually get around without having to be weighed down by all of those extra stresses.

“There’s also just a tremendous sense of belonging. Portland has done an incredible amount of placemaking, and so this photo [above] was just one of the little delightful little places I encountered while I was riding around and exploring.

[This is one of the places] where the community has really gotten involved and is really embracing the beauty and uniqueness of the spaces that are one-of-a-kind in Portland.”

“There was also this feeling of being cared for: there’s so many environments—I not only ride my bike but I also walk around a lot, and there are so many environments where the infrastructure tells you, ‘you don’t belong here, and in fact, we don’t even care how you’re doing.’ Right? When there’s no sidewalks, there’s no bike infrastructure, there’s actually no way to get around unless you have a car.

And it was an incredible feeling being in spaces like this where we would leave the hotel or we would leave the university campus and hop on our bikes, and it was like: there is a space for us, and somebody actually cares about how we’re doing and how we experience the space.

And finally, it was a hugely inspiring location. Portland has a lot of really beautiful architecture and a lot of artistic activity, but I also especially like this bridge—I spent several years of my life in an academic setting and this just gave me goosebumps: to see the motto [Let Knowledge Serve the City] on the bridge.

It’s a great aspiration, but it also, I think, reflects the orientation of PSU toward Portland: the research and the education they do really serves the city; it’s not just isolated in its own little thing. They really work to get out in the city and engage with the community and build things and improve things for the community.”

How did Portland come to be such a great place for biking?

-

Research & Collaboration

-

Community Activism

-

Political Will

“Bikeway design, like all traffic transportation planning and engineering, is at its heart very data-driven and technical. You really need to be prepared to dive into data and research. Portland State University, with people and professors and students who are highly invested in improving our system, has been a huge driver in Portland co-developing with the infrastructure it has.

Another component of course is community activism: people asking for more, expecting more and then getting out and making it happen.

That of course is tied closely with political will: I was kind of like, how did [Portland] turn out like this? And the professors said, ‘We just had some key people in the right place at the right time who are highly committed to making this happen.’

I stacked those up as kind of a list but it would have been good to draw them as an interactive circle, because they all interface and reinforce each other.

When we think about, “What do we do in our own community?” All of those pieces are tied together. When we put effort in community activism and advocacy, that helps drive political will. It helps bring more people into the circle and it also helps create a space where we can say: bring data to the table, bring in experts, and come up with the best designs for our own situations.”

Portland: often referred to as a cyclist’s dream

More about TREC, IBPI, & Devou Good’s Bike & Ped Scholarships

“Talking about the research and education piece: these acronyms:

TREC is a Transportation Research and Education Center which is based in Portland State University. IBPI (Initiative for Bicycle and Pedestrian Innovation) is one of their major programs focused around the bike and ped aspect of transportation overall.

The IBPI Bikeway Design Workshop has been held every year since 2009 and typically serves 15-20 participants, a meaningful and focused group. Many of them are planners and traffic engineers which is brilliant. Many of them come from all over the country and then can take that knowledge back to their own regions.

I also wanted to say thank you to Devou Good Foundation for the scholarship support—not only for myself but also for all of the other people from the greater Cincinnati region who have been sent to the workshop. Because it’s really a process of leveling up the knowledge and understanding to bring the best learning to our region.”

Learn more about Devou Good Foundation’s Bike and Pedestrian Workshop Scholarships.

“I like to tell people, this was the best workshop ever, because we’d spend half the day in lecture and half the day riding our bikes all over the city: it really can’t get any better than that.

Bicycle Facility Design: Who, Where, and What

“When talking about the context for bicycle facility design: there’s a lot of questions, but when you want to distill it into the big conceptual themes, there’s: Who, Where, and What.

Who are you designing for? [bear in mind]

-

Safety

-

Comfort

-

Consistency

[A lot of the “who” question is] filling in gaps in the network—for example, if someone is starting out in their neighborhood and there’s a path or trail that say they can have their 10-year-old son or daughter with them, but then two miles later they’re abandoned in some kind of, you know, traffic hellscape—that would not be a consistent experience.

“When you look at the who of who you’re designing for, you’re going to have a small, [2-3%] of people who fit into the strong and fearless category: they’re going to ride their bikes come hell or high water. It doesn’t really matter whether there is infrastructure, they’re going to figure it out and make it work.

Then you have [2-3%] of people who are enthused and confident: they will go the extra mile to make it happen and figure it out, but they also have a limit. i.e. I’m not going to use that road because it’s just too dangerous or unenjoyable.

Then, you have a very large percentage of people who are interested but concerned: they’re not riding their bikes even though they really want to. They’re feeling too much traffic stress, too much danger. There’s too many obstacles to connect from one place to another, and that is a huge, untapped group of people who really want to be riding their bikes but the infrastructure is getting in the way.”

A guiding principle, shared from lecture notes, is: Don’t plan for “cyclists”. Plan for people—especially those not yet riding: the “interested but concerned.”

Then you have where, which asks questions about:

-

Access

-

Equity

-

Connectivity

And what, which asks:

-

How do you choose the right types of bicycle facilities and treatments?

Portland’s goal is to: “Create a bicycle transportation system that is safe, comfortable, and accessible to people of all ages and abilities.”

Cunningham shared, “I think it’s really important to step back and think about how powerful those words are, because do we even dare to expect that most of the time? I think generally we’re immersed in this car-dependent, car-culture kind of infrastructure where that’s the water we swim in, when, no, it should be normal to have the structure that all ages and all abilities can get around on bikes.

Obviously we’re talking about bikeway design right now, but there’s loads of evidence that shows: when you introduce the features that make bikeway design safe, in the process you actually benefit everybody.

Changes in infrastructure make it safer for pedestrians, making it safer for people using strollers, wheelchairs or any other type of rolling device, and notably, the changes also make it safer for drivers.”

Another aspect of Portland’s policy is: “Create conditions that make bicycling more attractive than driving for most trips of approximately 3 miles or less.”

“Tying this to Cincinnati, over half of all trips in Hamilton County are under 3 miles, isn’t that amazing?! And 28% of trips are under one mile.”

This is where Cunningham shared that the who and the what are more technical pieces, emphasizing that participants spent four and a half days in lectures and she’ll only scratch the surface of what was discussed during the workshop. The goal is imagination: What kind of features are possible?

For more information on choosing the right design for the right location, tune into Cunningham’s recorded presentation. You’ll want to keep in mind: 1) neighborhood greenways (aka bicycle boulevards) 2) protected bike lanes and 3) signaling and intersection design.

Applying this to Cincinnati:

“Cincinnati has a lot of naturally quiet neighborhood streets. However, they often intermix en route with other local streets that have significantly higher traffic stresses.

Stepping back, really thinking with a network hat on, is to think about designating streets that are suitable for neighborhood greenways and actively managing them as opposed to just sort of having them sort of passively emerge.

Wayfinding: If you know me, you know I am a hardcore route planner. Around Cincinnati, I like to put a plan together before I go…in Portland, I was kind of like, okay, I want to get over to this area. I’ll just go, I know I can find my way.”

Again, check out the recorded presentation for core insights that can be applied to Cincy! I found it fascinating, informative, and full of nuggets that I’ll return to.

In closing, Cunningham’s conclusions and overarching principles were:

Whenever bikes and cars intermingle, safety is elevated by:

-

Visibility

-

Slow speeds (i.e. less than 25 MPH)

A note: less than 25 MPH is often indicative of protected bike lanes (PBLs)

Kathy Cunningham’s closing statements were met with loud cheers. It was a fun and informative event! Thank you again to our hosts, Humble Monk Brewing Company.